Mozart magical

- Lyn Richards

- Nov 12

- 5 min read

Updated: Nov 13

Die Zauberflöte premiered, in a popular theatre, 30 September 1791, two months before Mozart's death. Since then, it has defied simple summary, challenged directors to ever more exotic productions and casts of dancing animals, and delighted audiences with the magical story, the vivid imagery of the libretto and the extremes of the stunning music.

And it has continued to puzzle interpreters and leave first-time opera goers totally bewildered, while enthralling the singers who take these bizarre roles. This discussion at ROH gives a sense of their fascination. But it has also entered that strange category of a 'treasured holiday tradition'. The Met Opera now offers a cut version of Julie Taymor's production annually as a sort of operatic alternative to the Nutcracker. Check out the images from this beautiful production here.

The Magic Flute was different from anything else in Mozart's work.

Different because it was the only opera for which he helped create the libretto.

Different because it fitted none of the types - buffa? seria? - but combined them with new vaudeville celebration of magic.

Different because it was created and designed for a popular audience in a popular theatre, not for the demanding and constraining aristocracy. Different because it took the form of a Singspiel that combines singing with spoken German dialogue.

And different because, like his good friend who owned the theatre across the road and partner in these plans and achievements, (and the first Papageno!) Emanuel Schikaneder, Mozart was creating a musical celebration of Enlightenment. They were both Freemasons, (though Mozart was still a Catholic) and the symbols of the order net the opera.

Wiki has detail about the genesis of this work in myths and fairytales and political goals. And of course a formal synopsis.

What's the story?

Depends on what you are looking for. It is highly confusing and potentially ludicrous - here's Anna Russell to prove it so. But also fascinatingly complex, the themes held together in wonderful music that tells wonderful magical images.

The Metropolitan Opera first producted Magic Flute in 1900. The saga of their many gloriously cast productions since is here. Their new Opera House at Lincoln Center opened in 1966, featuring Die Zauberflöte designed by Marc Chagall - the only opera he ever designed - with a cast to wonder at. (Even Hermann Prey as Papageno - there's no recording available now, but here he is in 1975.)

The ways of looking at this opera are splendidly summarized in the following extract from OperaVision, reviewing a modern production placing the opera as a political statement.

The Magic Flute is often presented as a fairy tale about finding one’s way through the opposing forces of Good and Evil. Mozart’s last opera relates the trials and tribulations of two opposing yet complementary couples - Tamino and Pamina and Papageno and Papagena - who, in their search for love, journey through darkness to reach light and happiness. Along the way, they are accompanied by their magic instruments, which protect them from all sorts of dangers.

A magical farce

Many productions stage The Magic Flute as an earthy folk story in the tradition of the genre of the Viennese Punch and Magic opera (‘Wiener Kasperl- und Zauberoper’) in which mythical creatures occur side by side with real characters and good and evil forces compete over their influence on the protagonists until finally love conquers all.

Here, the mythical creature finds its embodiment in Papageno, who is himself more bird than bird-catcher. As a buffoon-like character who is clumsy and devious in equal measure, he delights the audience with his unpretentious folksy arias and is the source of much of the opera's heartwarming comedy.

Darkness versus light

While it initially appears as a magic farce, in the course of the action The Magic Flute increasingly turns to the proclamation of Masonic ideals, focussing on the duality of Enlightenment and obscurantism and highlighting elements of true heroism.

In the midst of their trials, the young lovers Tamino and Pamina are caught between the forces of the feminine and the masculine. The feminine force, the Queen of the Night, represents the moon, darkness, negativity, irrationality and chaos while her counterpart, the male Sarastro, stands for the sun, light, positivity, rationality and order.

The audience in Mozart’s day understood the political dimension of The Magic Flute very well. Its stance against feudality and the clergy had to be camouflaged and transformed into harmless events on stage. The elements of coarse Viennese comedy such as Papageno and the transformation of an old into a young woman can also be read in this light.

Navigating these different messages has tripped up most productions. Too much farce? Too many animals, too little celebration of the human love? A thoughtful review of the McVicar production's revival at ROH explains the challenges.

And the music

It's not all about the Queen of the Night, though her two amazing arias have dominated popular perception of the opera, and top sopranos have gloried in the impossible challenges of the music.

At the lower, lighter level, Wiki reports a Schikaneder story about the buffo duet moment when the bird-people find each other...

The late bass singer Sebastian Mayer told me that Mozart had originally written the duet where Papageno and Papagena first see each other quite differently from the way in which we now hear it. Both originally cried out "Papageno!", "Papagena!" a few times in amazement. But when Schikaneder heard this, he called down into the orchestra, "Hey, Mozart! That's no good, the music must express greater astonishment. They must both stare dumbly at each other, then Papageno must begin to stammer: 'Pa-papapa-pa-pa'; Papagena must repeat that until both of them finally get the whole name out. Mozart followed the advice, and in this form the duet always had to be repeated.

This is surely of Mozart's works the most varied and contrasted music - darkness and light, fear and love, play and violence, anger and peace. A brief introduction to the music is on the site of the Kennedy Centre (not yet renamed).

Our productions

We're starting with one of the simplest, and most praised, of the traditional productions. Directed by Jean-Pierre Ponelle and conducted by James Levine, at Salzburg in 1982, it is often described as a classic landmark production and revived many times. It's staged in the great arena of the Felsenreitschule, (a former quarry that became a riding school!) Extra scenery is minimal, costumes are 18th-century in a restrained color scheme. It's restrained, intimate - until the the Baroque excesses of the Queen of the Night do battle with the rational Neoclassical era of Sarastro and his priests.

Top performers were the women. Edita Gruberova was the Queen of the Night, Ileana Cotrubas made Pamina delicate, dramatically sensitive. Finnish bass Martti Talvela does Sarastro with heavy dignity, and Christian Boesch is an enthusiastic Tamino.

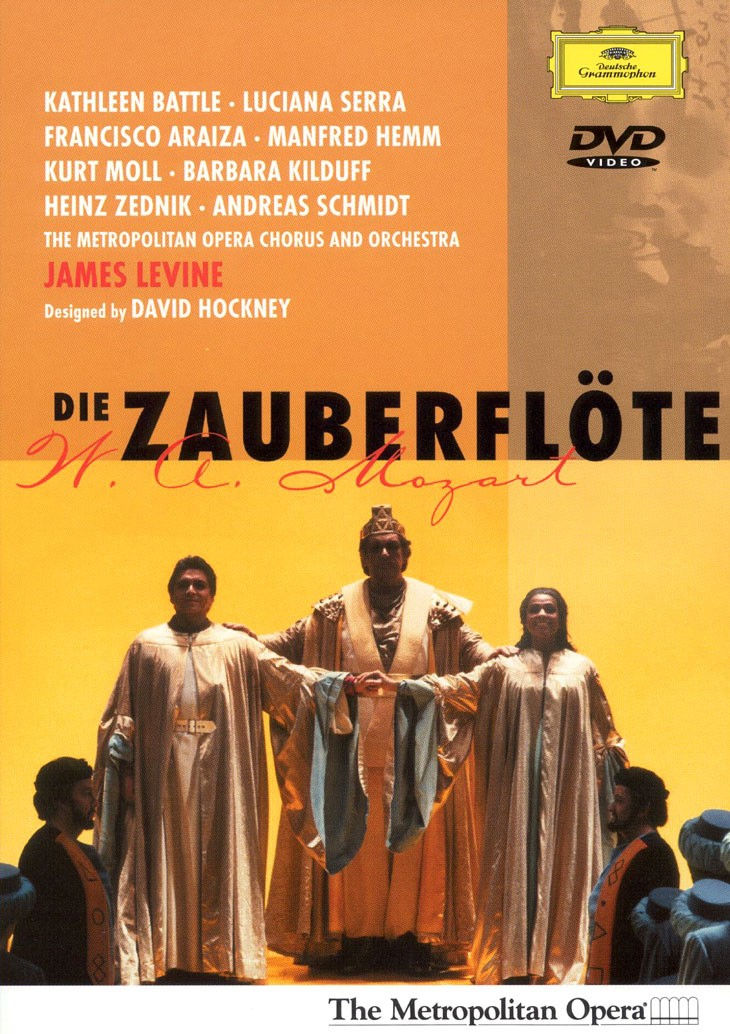

And then to the Met. We're playing their 1991 production, designed by David Hockney (a fair challenge to replace the Chagall design) and coming via Glyndebourne.

James Levine conducts, and stars are Kathleen Battle as Pamina, tenor Francisco Araiza as Tamino, and bass Kurt Moll as Sarastro. As it always is at the Met, there's emphasis on colour and shapes - and the patterned array of singers across the massive stage.

The New York Times review commented, “On this night, eye as well as ear was consistently beguiled. Mr. Hockney’s crazily colored sets and costumes evoked the mood of fairy tale innocence.”

Lyn, 13/11/25

Comments